Poles may save your knees, but at what expense?

The post The Weird, Very Real Danger of Approaching Climbs With Poles appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Anyone who hates hiking knows poles are your best friend. They can support part of your bodyweight to reduce the strain on your tired glutes and quads, they can stop you from keeling over when your pack feels like it’s equal to your bodyweight, and they can provide stability when teetering over loose rock. But poles can also break your bones. No, not from a fall—I broke my hand without ever hitting the ground.

How the injury happened

Washington Pass is a spectacular climbing area: it’s technically roadside, it’s not too crowded, and there are mountain goats everywhere. Unfortunately, depending on what climb you’re aiming for, you might be hiking anywhere from two to five hours a day to reach and return from your climb. The approaches range from decent single-track trails to steep, sandy talus.

On a particularly steamy summer’s day, my partner and I decided to climb Free Mojo (5.11; 800ft) on the South Early Winters Spire. It took us about an hour and a half to get to the base, and another hour and a half to hike back to the parking lot. I was using Black Diamond Distance Carbon FLZ poles—my favorite due to their light weight and three-part packability.

But that evening, when I got back to the car, I couldn’t move my left pinky finger. Maybe a weird cramp? A mild sprain? Was I just tired? By the next morning, the pain had surged throughout my hand, radiating into multiple fingers. Something was definitely wrong.

I rested my hand for a few weeks but saw no improvement. A physiotherapist assessed the damage, needled my hand (to promote relaxation and increase blood flow), and then sent me off with tape and more rest. Six weeks in, the pain hadn’t let up, so I called in reinforcements: Dr. Andrew Reed, a sports medicine physician at Banff Sports Medicine. He is also one of the more impressive endurance athletes in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, and a coach with Evoke Endurance. A quick Google search revealed he is also the lead team physician for the Canadian National Biathlon and ParaNordic ski teams. Surely he would know what was wrong with me.

Dr. Reed X-rayed my hand, assessed my wrist’s movement and associated pain patterns, and delivered his verdict: a possible hamate fracture and a sprained carpal ligament—likely the result of gripping and weighting my pole for multiple hours in Washington Pass, day after day.

Turns out, I wasn’t alone. Swapping injury stories with Brette Harrington, I learned that Marc-André Leclerc was sidelined for weeks due to a similar mechanism of injury, his forearm wrecked from constant pole use in Patagonia’s Torre Valley. Another friend of mine, who is a ski guide with the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides, had a wrist stress fracture after a winter’s worth of deep trail breaking in British Columbia’s Selkirk mountains. The more I asked around, the more I learned about pole-induced injuries.

How climbers can reduce trekking pole injuries

So if trekking poles can prevent us from climbing at all, what are backcountry climbers supposed to do—ditch poles entirely? My quads would stage a mutiny before I even left the parking lot. I started to pay attention to what poles endurance athletes were using on social media. Leki poles were particularly interesting: their “Trigger System” uses a breathable mesh that wraps around the meat of your hand, like a triangular fingerless glove, and ensures the impact of your poles, and your weight, is distributed evenly, reducing the risk of injury. The repeated, forceful pressure we put on our poles could perhaps be avoided with this technology.

Watch Emilie test the Leki CrossTrail FX One Superlite pole in Idaho’s Sawtooth mountains

Leki suggested I try out the CrossTrail FX One Superlite. Clocking in at under 6 oz per pole, it features a grip that is a “cross between a trail running grip and a more ergonomic hiking grip.” At first I was a bit hesitant to be clipped so securely to this pole, but within a few tries I mastered the release system. You can easily release the mesh glove from the frame by just pressing your thumb down.

There are only a few downsides to this pole. First, the fixed length. Unlike my OG Black Diamond poles, which offer roughly six inches of adjustability, the Leki Crosstrail locks you into a set size. Choose wisely. Second, durability. One tester took a pair to Patagonia, and while hiking in the Torre Valley, he slipped while carrying an overloaded pack and the Leki pole snapped with little protest. Given that the pole is made out of ultralight carbon, it’s not exactly shocking—but it’s a reminder that weight savings come with trade-offs.

I can’t promise that the Crosstrail’s glove system will keep me injury free (nor can Leki or Dr. Reed). But after weeks of testing in British Columbia and Idaho, my hand pain hasn’t returned. If Leki poles offer me a better shot at avoiding six-week spirals of medical appointments and x-rays, I’ll put all my chips on the table. And if that saves me from another existential crisis, I’ll call it a win.

Buy the Leki Crosstrail for $199

The post The Weird, Very Real Danger of Approaching Climbs With Poles appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Pro climbers and coaches Hazel Findlay and Angus Kille marketed “Strong Mind” as a way to manage my fears. And I had plenty.

The post Suffering From Climbing Anxiety, I Took Hazel Findlay’s Mental Training Course. Here’s What I Learned. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

The first time I led a trad climb, I placed a cam blindly and immediately took an uncontrolled, fearless, and absolutely exhilarating fall. I have great memories of that summer; 2019 was the season I began pushing myself on lead, ticked new grades, and fully dived into the climbing life. Crucially, I didn’t yet appreciate the consequences of climbing falls.

Fast forward six years and, thanks to a string of lower-body injuries, a bombardment of Weekend Whipper horror shows, and a few scary falls of my own, I now have a very different relationship to falling and risk. Nowadays, I am often stressed out about falling, and as a result I climb grades way below my physical limit. I also choose belayers very, very wisely. As my climbing-comfort plummeted, so has my self worth. Friends, strangers, and pro climbers all seem to be taking huge falls, pushing grades, and having fun while doing it. So why can’t I?

*

Hazel Findlay’s mental-training course, Strong Mind, is not a silver bullet. Strong Mind is mentally taxing, it strongly resembles therapy, and you will put yourself in situations you’ve been getting pretty clever at avoiding. The six-chapter course has 91 lessons, including “framing your mindset,” fear of falling/injury/exposure/failure, performance anxiety, and gives you actionable breathing and mindfulness tips. The depth of knowledge shared in the course is astounding—and is clearly created by two climbers with extensive experience pushing their own mental boundaries.

My favorite part of the course was doing a few practice falls at the crag, recording them, and getting analysis and feedback from Angus Kille. It was almost like the Strong Mind team was at the crag with me. In the video analysis, Kille pointed out that even taking small, clean falls made my body go very tense. And simple toprope bounces on the rope made me anxious—I was gripping my figure eight, a telltale sign I was uncomfortable.

I didn’t know how I felt about this information. I have the perception that I’m brave, that, as a trad and alpine climber, I like to take some amount of risk. Risk taking, I realized, was a big part of my identity, my sense of self. But do I actually like that risk? I began asking myself. Findlay addresses the nuanced fears (unrelated to climbing) that can affect your experience: failure, social comparisons, and performance.

In the fourth chapter, I began to do some deep thinking about the roots of my insecurities, and I learned that my fear of falling is equal parts fear of failure and reinjury. Neither fear will be solved by physiotherapy or strength exercises; I need to positively reframe my relationship to climbing by repeatedly having positive experiences with people I trust. These issues haven’t been resolved, but the team at Strong Mind helped me do my first giant leap towards having a better relationship to climbing, and myself.

Each week, participants have the opportunity to share their experiences with each other. Eventually I mustered the courage to talk about my experience with injury and how it has completely reframed my outlook on falling. So many classmates identified with my discomfort and simply said “same.” I don’t think there is a more comforting response when speaking about your trauma or insecurities.

Of course, the roots of your fears or insecurities may be completely opposite to mine, and different chapters may resonate with you while they didn’t resonate with me. The 91 lessons dive into a range of topics, and it is totally worth your time to explore them all. Nothing worthwhile ever comes easy, right?

*

The Strong Mind course’s main downfall, in my opinion, is the mountain of content that’s shared in such a short timeframe. The course is meant to be completed in just eight weeks—including going out to the crag between classes and implementing its teachings—but after a few weeks of listening to videos online, participating in the asynchronous forums, and trying to join weekly Q&A sessions (which were always, it seemed, smack in the middle of my mountain-standard-time workday), it was all too much. I didn’t feel like I had enough time to go out and actually practice falling, and I certainly didn’t have time to reflect on what I learned before I started the next chapter. Just like my inability to take big, safe falls, I soon felt like I was failing at this course too.

The course’s frantic pace, paired with stressful life events, seemed like too much so I slowed my roll. After all, students have lifetime access and there was no point in rushing the learning process. I took my time with the course and finished it in the fall, when Canada’s all too brief summer ended and I had time to work the material at my own pace.

So I spent the better part of last autumn taking practice falls, breathing deeply above my gear, taking in the view at the top of the pitch, and remembering what it feels like to enjoy climbing. In my mind, it’s 2019 again, and I’m eating gummy bears in a comfy belay parka at my favorite crag. I’ve come down from sending a few hard-for-me pitches teary eyed from joy and, of course, the dopamine hit. I’m enjoying myself again.

Hazel and Angus warned that this is an ongoing process of unlearning and relearning—it’s not over! But I’m glad to now have the tools to cope.

The post Suffering From Climbing Anxiety, I Took Hazel Findlay’s Mental Training Course. Here’s What I Learned. appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Neil Gresham is an elite climber and coach, but he specializes in training V2-V6 mortals.

The post Coach Reviews: Neil Gresham Trains Intermediate Climbers—and He’s Dang Good at It appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

In February 2022, I took a nasty tumble down a backcountry couloir in the Canadian Rockies. I received two things from that experience: a sick view of the North Face of Mount Temple from the chopper, and an osteochondral lesion, which takes a minimum of two years to heal. I’ve climbed plenty since that accident, but it has always been in pain, and I’ve struggled to climb with any consistency to actually make strength gains. So when the opportunity arose to be coached by Neil Gresham, I eagerly volunteered. I’ve had a hard time finding inspiration of what exercises I could do to remain active since my ski accident, and I had little interest in becoming a meat-head weightlifter. But Neil assured me he could help me out.

Although Neil is an elite rock and ice climber, he specializes in training climbers in the V2-V6 range. Neil agreed to develop a plan for me that catered to my very specific needs: no weight bearing exercises on my feet and no climbing (I couldn’t risk a small bouldering fall and have to restart my recovery). Even the physio-approved cardio exercises I could do were limited. Nevertheless, he developed a plan for me to strengthen every able-bodied muscle and tendon I had, with an emphasis on fingers and core. Neil’s plan was delivered to me in a 25-page PDF, which I opted to print out, and was divided into three-week blocks: base conditioning (to ensure I was fit enough to endure the inbound program), strength (low repetitions, high weight to failure), and endurance (lots of reps, minimal weight). Throughout the 12-week program, Neil sprinkled in cardio exercises (if you can do them, at least), intense abdominal circuits, and antagonist workouts.

The entry-level program that I chose (at an affordable $115 USD) doesn’t include much testing, and you don’t get to chat with Neil on a day-to-day or weekly basis about how the workouts are feeling, or if they can be adjusted. Neil tests three things before developing a personalized plan: how many pull-ups and toes-to-bar you can do until failure, and how long you can do a half-crimp deadhang on a 20mm edge. This tier of coaching doesn’t include climbing-movement reviews, or any other interaction after the initial assessment period. That said, Neil does offer an increased level of support. Go check out his website for all of the different tiers offered.

There are obvious drawbacks to an asynchronous plan and a limited assessment period; I found myself regularly updating the rep counts and adding weight. For example, despite the fact that I began the program hanging from a 20mm edge for 10 seconds with an additional 120 pounds, the program indicated that I should remove some weight while max-hanging for strength. However, Neil does include plenty of tips and instructions for how to adapt your plan to make it easier or harder—so just pay attention to what feels tweaky or way too easy (for the goal of the exercise) and adjust as necessary. The plan will give any V2-6 climber the inspiration, structure, and confidence needed to be active seven days a week and hangboard 3-4 times a week (provided you’re not supplementing that with actual climbing).

Going into this program, because I wasn’t sure if my foot would allow me to climb by its end, my goal was to generally improve my upper body fitness, namely my lack of pulling power. After 12 weeks, I increased the repetitions of body weight pull ups by 66% (from three to five reps), my toes-to-bar by 33% (from six to eight reps), and my half-crimp deadhang by 105% (from 12 seconds to 24.7 seconds). I can’t tell you whether I sent my project, because I’m still not out of the woods, but you get the idea—if I could climb, I’d be sending.

Overall, I was impressed by Neil’s ability to craft a plan that was adapted to my very specific restrictions, and one which still felt targeted to my goal of ultimately climbing harder outdoors. As someone who maxes out at 5.12 and WI 5, I had no shortage of imposter syndrome when hobbling into the gym last November for a “performance climbing plan.” His plan proved that, despite my injury—and my lack of a training history—I still belonged there.

The post Coach Reviews: Neil Gresham Trains Intermediate Climbers—and He’s Dang Good at It appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

Each January we post a farewell tribute to those members of our community lost in the year just past. Some of the people you may have heard of, some not. All are part of our community and contributed to climbing.

The post A Climber We Lost: Leo Grillmair appeared first on Climbing.

]]>

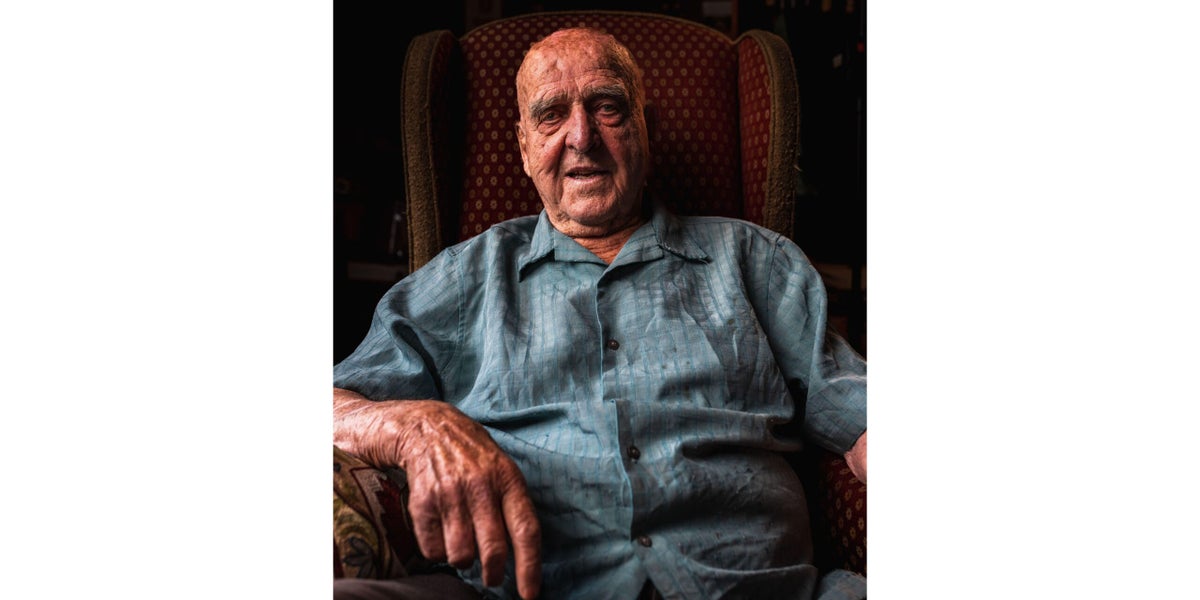

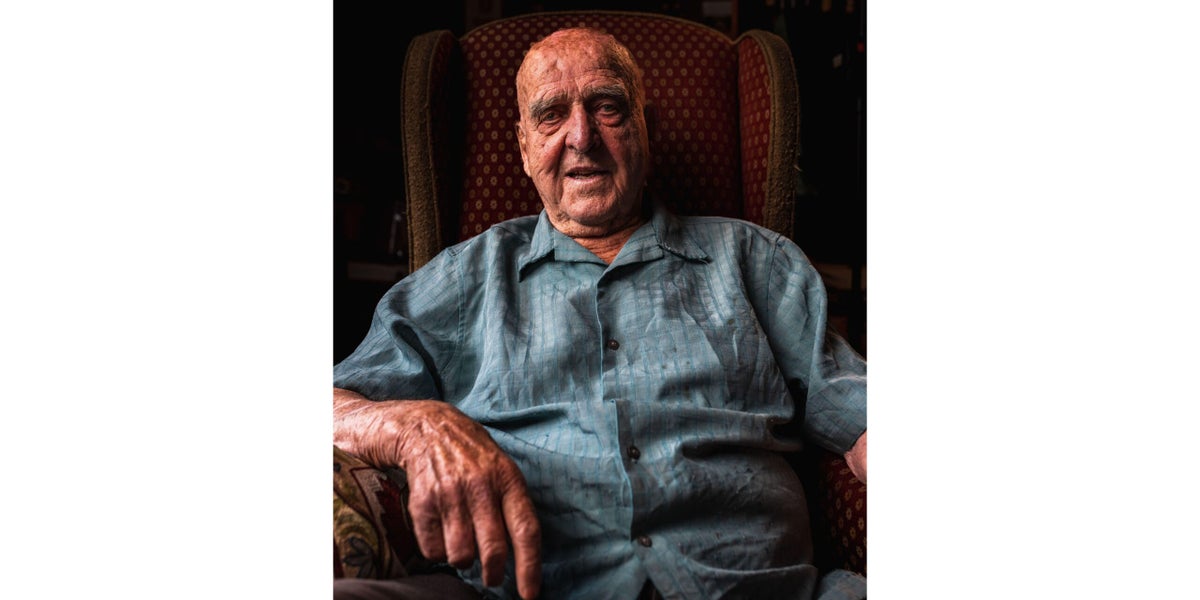

Leo Grillmair, 92, May 1

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2023 here.

Leo Grillmair, a legendary mountain guide, heli-skiing pioneer, and co-founder of both the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG) and Canadian Mountain Holidays (CMH) Heli-Skiing & Summer Adventures, passed away on May 1, 2023, at the age of 92. Leo succumbed to injuries sustained in a skiing fall.

Leo was born on October 11, 1930, in Ansfelden, Austria. His passion for mountaineering took root early, as a young boy, learning to ski, camp, and hike with mentors from the area.

After the second world war, Leo seized an opportunity to move to Canada, when he was just in his 20s, convincing his childhood friend Hans Gmoser to join him. After injuring a leg and getting fired from a few jobs, it was Leo’s perseverance and love for the mountains that ultimately brought them to Calgary where they could explore mountainous landscapes. Leo’s technical skills, combined with his passion for skiing and mountaineering, marked the beginning of an extraordinary life in the mountains.

Leo and Hans soon found themselves in the Bugaboos, British Columbia, drawn in by stories from fellow Alpine Club of Canada members, who spoke of stunning gray and gold granite spires that rose up from pristine glaciers. Leo and Hans were rapt. Through guiding clients, they came up with the idea of using helicopters to quickly gain more vertical. In April 1965, they officially launched commercial helicopter skiing, giving birth to the activity and, consequently, opening CMH Bugaboo Lodge in 1968. Leo’s role in CMH ran deep. Aside from co-founding the company, he spent 22 years as area manager and lead guide in the Bugaboos. Leo’s contribution to skiing and climbing went beyond his business; he pioneered new routes, including the iconic Grillmair Chimneys (5.6) and Direttissima (5.8+) on Mt. Yamnuska, made the first Canadian ascent of Mount Alberta, and put up a new route on Denali, in Alaska, among many other accomplishments. In a 1997 interview with Chic Scott, Grillmair recounts jumping from a cliff face to a hovering helicopter 500 or 600 feet up in the air to avoid rappelling from shoddy pitons with a “rucksack full of rocks,” catching himself on the doorframe of the helicopter.

In his later years, Leo retired to his property in the Columbia Valley near Brisco, British Columbia, not far from the Bugaboo heli-pad. He said, “I often think, ‘do born Canadians really appreciate what they have here? Do they know what they have?’ I don’t think so. … We take a lot for granted, but we shouldn’t.” Leo remained connected to CMH, and regularly visited the Bugaboos. As told by Kelsey Verboom, his legacy lives on in the hospitality and warmth that defines CMH, a testament to his enduring impact.

Leo’s life unfolded as an extraordinary odyssey, transitioning from a modest dwelling in Austria to the majestic summits of Canada. His adventurous spirit, pioneering vision, and unwavering dedication have left an indelible mark on the world of heli-skiing and mountaineering. As friends and admirers fondly remember Leo, his legacy will continue to inspire generations to come.

The post A Climber We Lost: Leo Grillmair appeared first on Climbing.

]]>